Not Eudora

By Harry Welty

By Harry Welty

Published May 26, 2005

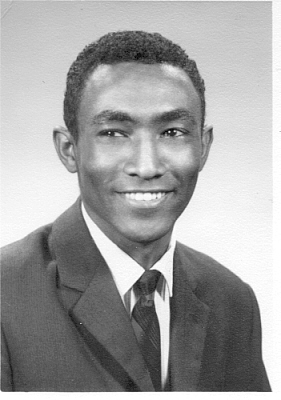

Bedru Beshir Mohammed Desta Beshir 1948-?

Bedru

There is a story about Bedru that I would tell if I knew for certain that he was

dead. But Eritreans are a proud people and should my telling of the tale ever

come to his attention I could not be sure that he would forgive me. He held fast

to one grudge back in 1968 the year he lived with my family. A teacher's

innocent remark which made a classroom burst out laughing burned in Bedru's

heart until the end of the school year. Mr. Wilker, one of my favorite teachers,

was crushed at year's end to receive Bedru's angry letter accusing him of

racism.

Years later when I tried to learn my old roommate's fate I discovered that my

Mother had thrown out all the letters he had sent my parents after his return to

Ethiopia. They made her feel guilty as though our family had abandoned him. We

did. This was the last thing I could have expected when our local AFS Program

(American Field Service) announced that no families had volunteered yet to host

the next year's male foreign exchange student.

I don't know what possessed me to ask my parents if they would be willing to be

hosts. I was dumbfounded when we filled out the application. When my Mother

expressed reservations about answering "yes" to the question about our

willingness to host a student from a different race the rest of us shamed her

into going along. Not long afterwards we were informed that our student would be

from Ethiopia. He would be an African. Not only that, he was also a Muslim.

Never in anyone's memory had Mankato High School enrolled a black student or for

that matter a Muslim.

We picked Bedru up in the Twin Cities shortly before school started and peppered

him with questions on the drive home that he could not answer. However well he

could read English he could barely speak it. It would take a few months before

he was fluent enough to get by and it was probably during this time that he

concluded Mr. Wilker had mocked him in front of his classmates.

Bedru was smothered with a lot more "Minnesota Nice" than racism in

Mankato. I once saw an acquaintance mouth "Black Boy" as he stared at Bedru in a

crowded hallway but I was the only one who noticed. Most Mankato kids were

simply curious about our exotic guest. We didn't have any snow that year (if you

can believe that!) but a gang of sophomores took him snowmobiling on a frozen

lake. Poor Bedru only wore leather street shoes on that expedition and got very

cold toes. It was another escapade, this time with some of Bedru's fellow

seniors, that I can't bring myself to write about. But even here juvenile

curiosity seems to have played more of a role than anything mean-spirited.

While racism was not an overwhelming factor in his stay it was a factor. Bedru's

attraction to one of the cheerleaders was awkward. She reluctantly agreed to go

to a movie with him even though she had a steady boy friend. She didn't want

Bedru to think she was a racist. This was the kind of racism we encountered; the

kind where people bent over backward to prove they weren't racists. To her

credit Pam was probably the first white girl to "date" a black man publicly in

Southern Minnesota during an era when a dozen states would have jailed them for

breaking the law. However, there were limits. When he asked her if she wanted to

kiss him she declined. That would have been disloyal to her boyfriend. Bedru was

a little put out after the date probably because he had gotten a lot of his

ideas about western women from characters in the James Bond movies he'd seen

back in Ethiopia, characters like Pussy Galore.

Although my family had placed an arrow facing Mecca on the floor of our bedroom

Bedru told us that the Prophet excused traveling Muslims from praying while in

foreign lands. I got the impression that Bedru felt he could store up his

neglected prayers and fulfill them all upon his return home. We had one close

call over his eating pork during one school lunch but the cooks assured us that

the hot dog he'd consumed had been made with beef. Frankly, I don't think

he missed his religious duties any more than most kids miss attending Sunday

school.

Despite nuisances like frozen toes and mayonnaise Bedru was probably more at

ease in Minnesota than he had ever been in Eritrea. He relished our secular

freedom. His ambition was simple and universal. He wanted to attend college and

make a good life. He hinted strongly that he would have liked to stay in America

to attend college. This hope greatly troubled my parents.

Had he been allowed to stay my parents would have felt obligated to host him for

another four years but that's not what they had signed up for. AFS rules spared

them this worry. Owing to the reluctance of foreign nations to lose their most

talented students in a "brain drain," AFS students were required to return home

when their school year ended. My father, a lawyer, held firmly to this part of

Bedru's contract. No doubt the INS would have backed him up.

Whatever fate awaited Bedru back home in 1968 it didn't seem a whole lot worse

than what was happening in Vietnam War plagued America. In April Martin Luther

King was assassinated and riots broke out in dozens of our largest cities.

Being an African this calamity did not affect Bedru the same way it affected

black Americans. Having grown up in Africa with nothing but Africans around him

he had not been made to feel inferior to white people. But having been raised in

an authoritarian colony Bedru did identify with our nation's Democratic

evangelism. President Kennedy's Peace Corps program had sent several dozen

American volunteers to Bedru's hometown and he greatly admired the martyred

President. When Kennedy's younger brother, Robert, began his charge for the

White House Bedru followed his campaign even more avidly than my politics

obsessed family. The rest of us went to bed the moment Kennedy's victory in the

California primary was announced. Bedru stayed glued to the television. He turned the

lights out and went to bed quietly that evening without waking us with the news

that he had just seen Bobby Kennedy's murder. He returned to Africa a few days

later.

Notwithstanding these horrors Bedru's visit to America gave him a glimpse into a

world of possibilities. Sadly, his Minnesota adventure caused him to forfeit his

opportunities back in Ethiopia.

Mussolini's conquest of Ethiopia in 1936 was launched from Eritrea an Italian

colony on the Red Sea. After the Second World War the UN awarded the "protectorate"

of Eritrea to Ethiopia thus giving landlocked Ethiopia a seacoast and a large

Islamic minority. Ethiopia was an ancient Christian kingdom. From the moment of

their annexation Eritreans set out to gain their independence.

While in America Bedru was safe from the conflict. He had studied five languages

and fully intended to attend the University in Addis Ababa. But while Bedru

learned spoken English in the United States his facility with Ethiopia's

national language, Amharic, withered. When he took the entrance examinations

back home he failed Amharic. His letters to us complained bitterly that less

deserving students could gain admittance by bribing government officials.

The day Bedru arrived in Minnesota I had asked him eagerly about his wonderful

emperor, Haile Selassie, so famous in the West for his brave but futile stand

against Mussolini's invasion. Before the year was over I came to realize that

our "hero" was Bedru's oppressor. After taking command of English he remained

circumspect about Selassie. There was no telling what kind of dossier Ethiopian

agents might be keeping on Bedru, one of their own "foreign" foreign students.

Long after our last letter from Bedru I found a slip of paper with some notes

Bedru had jotted down. Some of the notes were written in Triginian his native

tongue but he had written down his options in English. His first option was

attending the University which of course had not panned out. His second option

was to find a job which he was eventually to do. His third option was to join

the EPLF. The EPLF was the Eritrean People's Liberation Front. Next to this

option Bedru had written the names of five Eritrean friends.

Although the letters to my parents are lost I still have four letters that Bedru

sent to me. I'm embarrassed to admit that I didn't write back to him very often.

I was too busy enjoying all the opportunities that he was denied. The last

letter he sent my parents was mailed in 1972 and it was the one I was

specifically looking for. It was oddly vague and read as though he was trying to

get it past censors. Since his written English was already labored this letter

was very cryptic indeed. He told us that he was in a dark place by himself with

only a small friend to keep him company. My Mother said it sounded as though he

was in jail feeding left over crumbs to a mouse.

The war between the Emperor and the EPLF continued to heat up after Bedru's

return. Since educated and ambitious natives are always viewed suspiciously by

their colonial masters it wouldn't be at all surprising if Selassie's government

did jail Bedru. The notes I found certainly hinted at his disloyalty. A decade

later Selassie himself would be murdered in a coup. A clique of military

officers with the ominous sounding name, the DIRGUE, would plunge Ethiopia into

an even more rapacious war against Eritrean rebels. They unleashed a man made

famine in the mid 1980's which starved a million innocent people to death many

of them Eritreans. How Bedru could have survived that decade I can't imagine.

It's been over three decades since Bedru and I shared a room. I've had the

luxury to live a life he might have imagined but never got the chance to enjoy.

I've tried not to take my good fortune for granted.

Welty is a small time politician who lets it all hang out at: www.snowbizz.com